Three major Canadian cities – Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver – have enacted inclusionary housing policies. Although different in many ways, the policies share a number of key features that provide the basis for a limited but effective made-in-Canada inclusionary housing approach. This paper describes and compares those policies, and identifies their key shared features.

The preparation of these case studies was funded by the Wellesley Institute.

This approach falls short of mandatory inclusionary zoning as practised in the US. It can be seen as encompassing a set of practices that can be utilized within the current municipal powers in this country, and until municipalities are able to implement more demanding and comprehensive provisions.

SUMMARY OF THE THREE POLICIES

All three of these policies are directed at providing mixed-income housing in developments that otherwise would contain only market housing.

The following provides a summary of each of the policies. The policies are also examined in greater detail in separate case studies.

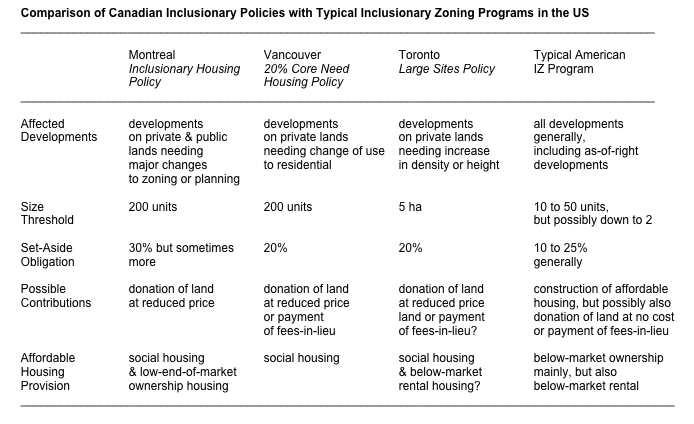

Comparison of the Three Canadian Inclusionary Policies with Typical American IZ Programs

Montreal’s Inclusionary Housing Strategy

This strategy – formally called a ‘strategy for inclusion of affordable housing in new residential projects’ – was adopted by the city in 2005. It is the most comprehensive and productive of the three policies.

The strategy’s goal is to provide at least 30% of the new units as affordable units in major residential developments – half as social housing and half as affordable rental or affordable ownership.

It is applied to developments of 200 and more units because they are considered capable of accommodating a mix of housing generally, and also a viable social housing project.

The strategy is applied mainly to developments needing a major change to planning and zoning provisions, such as a change to the permitted land-use, density or height. It applies to privately-owned lands, and also to lands owned by governments and public agencies whenever released for residential purposes.

The strategy was designed to provide suitable development sites for social housing built through government funding, and the construction of “low-end-of market” affordable ownership and rental housing built by private and possibly non-profit developers.

This approach is aptly called a strategy because it must operate within Montreal’s two-tier government. The strategy was established by the city-wide government, but depends upon its constituent boroughs for implementation because the control local planning and development approval.

Vancouver’s 20% Core Housing Need Policy

The city introduced an inclusionary housing program in 1988 through a policy originally called its ‘20% core need housing policy’. This policy is the most straightforward of the three.

This policy is applied to large privately-owned developments seeking a change of use to residential. It affects only developments of more than 200 units because these are considered capable of accommodating a separate and reasonably-sized social housing project.

These developments are required to provide sites capable of accommodating a minimum of 20% of the units as social housing, and half of that as housing suitable for families.

The policy was designed to provide suitable sites for the development of social housing through government funding programs.

Toronto’s Large Sites Policy

The basis for Toronto’s corresponding inclusionary housing approach is provided by the ‘large sites policy’ of its Official Plan. The policy was approved in 2002, but did not come into effect until mid-2006.

This policy is the least developed of the three. It has not been used, nor have any implementing regulations been prepared to expand upon the basic OP provisions.

Under this policy, on residential developments on sites generally greater than 5 ha, when an increase in the already permitted height and/or density is sought, the provision of 20% of the additional residential units as affordable housing will be the city’s “first priority community benefit”.

The policy has been designed to make use of section 37 of the Ontario Planning Act, under which the city is able to offer an increase in the permitted height and/or density in return for the provision of various “facilities, services or matters”, otherwise generally called community benefits.

The policy identifies alternative ways for meeting the affordable housing obligation. Based on various considerations, it can be expected that the obligation will be met mostly by the conveyance of development parcels on the large sites rather than the construction of affordable housing, and these parcels will be used to support mainly social and possibly affordable rental housing built with government funding.

SUMMARY OF THE KEY PRACTICES

Shared Practices

These city policies all incorporate a number of practices that provide the basis for an effective inclusionary approach.

These policies provide an effective inclusionary approach, in the first place, because they are able to impose the affordable housing obligation on the developers of the selected projects. The obligation can be successfully enforced by the denial of the development approval to these projects that do not comply. Unless the developers are able to appeal the denial to some higher authority, they have no choice but to meet the obligation if they wish to develop.

At least two of these policies, if not all three, also share to some extent key practices. (It is not possible to say conclusively that Toronto’s policy when implemented will incorporate all of these practices, but it seems very likely that it will.) Those practices include the following:

- leveraging an approval for a major change in the development regulations to impose the affordable housing obligation;

- imposing the obligation on developments large enough to accommodate a separate project for social housing;

- securing the contribution of a developable site at a reduced cost for the social housing; and

- relying upon senior government funding as the primary source of subsidy for the social housing.

Other Practices

Montreal’s strategy has introduced two other key practices not seen in the other two, but these are very important for extending the effectiveness of these inclusionary policies. The additional practices are these:

- applying the inclusionary housing obligation to publicly-owned lands, and not just to the privately-owned; and

- including affordable rental and ownership housing, not just social housing, in the potential housing mix.

COMPARISON WITH INCLUSIONARY HOUSING

The inclusionary practices followed in inclusionary zoning programs in the US are different in than those in the three Canadian policies in a number of significant ways:

- They exploit the development approval to achieve substantial price reductions for the affordable housing. This approach does not rule out the use of government funding to achieve still deeper subsidies, but it does means these programs are not dependent upon government funding to provide affordable housing.

- They impose the affordable housing obligation on all new residential developments, including generally those built as-of-right within the existing regulations. When small developments are excluded, the cut-off is generally for developments in the range of 10-50 units.

- They require the private developers to build and provide the affordable housing. The provision of sites or cash-in-lieu is often permitted, but generally only at the discretion of the municipality and where they achieve a greater benefit.

- They generate “below-market” affordable ownership, and sometimes rental, housing. This is housing that is provided at price or rent that is substantially lower than that available for the equivalent housing on the market.

- They ensure that the affordable ownership housing remains “permanently affordable”. Controls are used to protect the below-market price whenever the units are resold for a very long time or even permanently.

- They mix the affordable units within the market units, and generally design them in a way that makes the two largely indistinguishable.

The principal consequence of these provisions is that inclusionary zoning programs, in comparison with three Canadian policies, are able to effect the actual construction of affordable housing, and also to produce that housing on a much wider range of development sites.

One potential criticism of inclusionary zoning is that it does not support the provision of social housing. While this is true for most programs, it does not mean that inclusionary zoning is inherently incapable of doing so. Indeed, there are programs (see the inclusionary zoning program in Davis CA) that are similar to three city policies; they are designed to provide development sites at no cost for government-funded social or special needs housing in mixed-income projects.

Reasons for the Differences

The adoption of the more limited approach in the three Canadian cities is conditioned by certain considerations particular to this country:

- The lack of express legal authority in provincial legislation to impose a full mandatory affordable housing obligation. As a consequence, cities are barred from requiring developers to provide affordable housing when they develop within the existing permitted zoning.

- The enduring conviction that the provision of affordable housing is fundamentally a problem that can only be addressed by federal and provincial funding. So, municipalities generally do not feel compelled to utilize their regulatory powers to support other forms of affordable housing.

- The related conviction that supporting affordable ownership is not serving an important or legitimate housing need. Therefore, promoting this form of housing is seen to be a misuse of energies and resources.

RD/15Jan10

Leave a Comment